When red is the colour of hope: 46 years on, Surovi School’s dream factory stands strong

When red is the colour of hope: 46 years on, Surovi School’s dream factory stands strong

Founded in 1979 with just one domestic worker as its first student, Surovi School today stands as a sanctuary of hope for hundreds of marginalized children — driven by a visionary woman’s quiet resolve and tireless fight against inequality

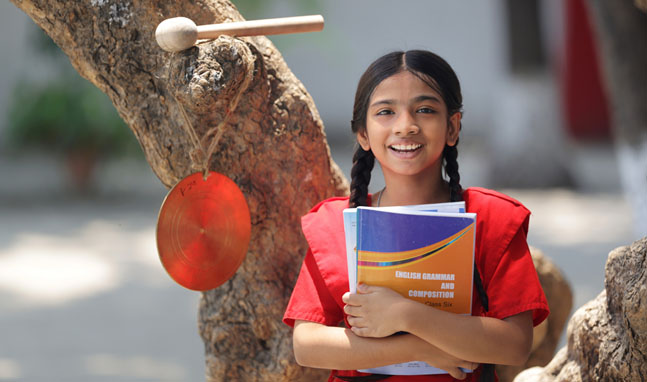

Push open the red iron gate of Surovi School in Dhanmondi 5 on a weekday morning, and you will step into a world awash in crimson — red uniforms, red carpets, and hopes glowing bright in little hearts.

On the left side of the spacious school premises, in front of a single-storied office building, children sit cross-legged on mats beneath the shade of trees — their voices rising in unison as they recite poems, or they are quietly immersed in drawing pictures.

To the right, makeshift tin-shed classrooms, open on one side, also hum with the rhythm of learning. Teachers chalk lessons onto blackboards, then move gently between rows of students like attentive gardeners, tending to each budding mind.

It is here amid this hubbub that we meet Mohammad Rony Mia, a fifth grader with bright eyes and a smile full of quiet confidence. His father is a rickshaw-puller, and his mother is a domestic worker.

For children like him, dreams often take a backseat to survival. But not for Rony. Social Sciences is his favourite subject, and his "aim in life is to be a doctor," he says shyly, yet his eyes sparkling. "I'm usually one of the top three in my class."

| "The children don't

come from privileged backgrounds. Their lives are shaped by hardship and

poverty. Most of their parents aren't even concerned about their education.

Yet, they come to school — driven by a dream to change their lives, to rise

above their circumstances." |

Israt Jahan Lita, Headmistress, Surovi School

Tithi Islam, a class six student, shares the same determination. Her father is a construction worker, and her mother stays at home due to severe illness. "When I grow up, I want to take care of my family," she says. "I want to make sure they never have to struggle again."

According to the headmistress Israt Jahan Lita, the school currently has 462 students enrolled across two shifts, from pre-primary to class 10. The first shift runs from 8:30am to 10:30am, and the second from 11am to 2pm.

There are 11 teachers at present, working for nominal pay. "They are the backbone of this school. Despite a meagre pay, they teach with a deep sense of purpose," Lita says with pride.

"The children don't come from privileged backgrounds," Lita continues. "Their lives are shaped by hardship and poverty. Most of their parents aren't even concerned about their education. Yet, they come to school — driven by a dream to change their lives, to rise above their circumstances."

In all, over the past 46 years, Surovi has provided literacy and learning opportunities to nearly 2.8 million children. Photo: Mehedi Hasan

Considering that many of these children receive little to no support at home and are often unable to complete their homework due to having to work for a living from a young age, such results are indeed remarkable.

Part of the motivation comes from the support they receive. Education here is entirely free. In addition, through a sponsorship programme, the school provides students with educational materials, food, school uniforms, regular clothing, household essentials, cleaning supplies, rent assistance, and medical expenses — distributed quarterly.

Furthermore, under its scholarship initiative, the school offers financial assistance to talented students from underprivileged backgrounds pursuing secondary, higher secondary, and even tertiary education, ensuring they can continue without interruption despite financial hardship.

Haque adds that not all students live nearby. Some travel from as far as Mirpur, Rayerbazar, Mugda, and even Kamrangirchar just to study here.

"We don't need to advertise," Haque says. "The red uniform speaks for itself — everyone now recognises a Surovi student. During admissions this January, there was a long line of applicants. But we carefully selected 150 children — those truly from marginalised, underprivileged communities."

"And we are inclusive," adds Lita. "Children of all religions, ethnic minority groups, and even those with disabilities study here. Everyone has a place."

And so has this place been since 1979, when Syeda Iqbal Mand Banu, a renowned social worker and philanthropist, founded Surovi to provide education to marginalised children.

Banu, now 84, is a truly versatile figure. She completed her master's degree from the University of Dhaka and also earned a degree in Fine Arts from Charukola. She is a painter, a writer, and a trained pianist.

Her personal life, too, has intersected with significant national figures. She was married to the late Rear Admiral Mahbub Ali Khan — who once served as the Chief of the Bangladesh Navy and later as Minister for Communications and Agriculture. Her younger daughter, Dr Zubaida Rahman, is the wife of BNP's acting chairman Tarique Rahman.

Ironically, though she has never been involved in politics herself, her family ties have subjected her to harassment during the Awami League regime — including a lawsuit filed against her by the Anti-Corruption Commission on the grounds of "failing to submit a statement of assets within the stipulated time".

Yet none of that halted the journey of either her or Surovi, which began on 1 February 1979 with a single student named Shanu — then working as a domestic help in her own home.

It was at 16, Road 5, Dhanmondi — her family home inherited from her mother — that she founded Surovi. To continue funding the school, she even sold her personal jewellery.

At the organisation's 46th founding anniversary celebration on 1 February this year, this publicity-shy woman shared, "When I was young and went to school, I used to see many children who didn't. I would ask why they weren't going. My mother would say, 'You start something — then others will follow.' When the opportunity came, I started Surovi."

And just as Surovi means "fragrance," her work quietly spread its essence far and wide.

While the Surovi School in Dhanmondi is largely sustained through Syeda Iqbal Mand Banu's personal funding, the organisation itself has grown significantly over the years. Since its inception, Surovi has expanded operations across all 8 divisions of Bangladesh, reaching 35 districts and 75 upazilas.

Its work goes beyond general education, encompassing vocational and technical training, early childhood development, water and sanitation, child rights and protection, disaster risk reduction, emergency response, and more.

In all, over the past 46 years, Surovi has provided literacy and learning opportunities to nearly 2.8 million children.

In recognition of her remarkable contributions to social welfare, Banu was honoured with the country's highest civilian award — the Independence Award — in 1995.

She has also received the Kazi Mahbubullah Trust Gold Medal, Nipa Shishu Foundation Gold Medal, Atish Dipankar Award, Chandrabati Padak, Kamalkuri Padak, Sandhani Padak, Anjuman Mufidul Islam Award, and the Azizur Rahman Patuari Award, among many others.

Md Abu Taher, executive director of Surovi, is optimistic that their efforts will persist. But he does not ignore the cruel realities of today's world.

"We want to give these children a beautiful future," says Abu Taher. "But the older they get, the more they tend to drop out because once they reach a certain age, their parents expect them to start bringing money home."

To earn that money, not all turn to lawful means of livelihood. Some start by trafficking drugs, eventually falling into addiction themselves. Others become involved in various unethical and criminal activities. And then, there is the issue of child marriage, which remains a major contributor to the high dropout rates.

"Another big concern these days is mobile phones," he continues. "Everyone has one now. But children of educated, aware parents usually stay in control even with a phone in hand – many use it just for study purposes. Now think about these marginalised children whose parents aren't aware – how vulnerable they are because of mobile phones!"

It is critical to protect vulnerable children from a life of exploitation. That, he believes, is precisely why spreading the light of education among underprivileged communities is now more urgent than ever. "With Surovi, we hope to keep doing just that," Abu Taher concludes.

Get in touch!

Address

-

SUROVI, House # 16, Road # 05, Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka-1205, Bangladesh.

-

(+880-2) 44613637

-

info@surovi.org, surovi69@yahoo.com